The twelve year old boy I will call Tshering began to suffer panic attacks after a girl in his class died. He is from a small village in the eastern part of Bhutan. Dr. Allen, the HVO volunteer psychiatrist, one of two psychiatrists in the country, asked me to see him. It was about a week after I had arrived in Thimphu.

I had already given my first lecture on hypnosis to children, to the Pediatric residents, interns and attendings, on my first full day at JDW National Referral Hospital. After quickly dispelling myths about modern clinical hypnosis - No, it is not like the hypnosis show you saw in India - No, it is not a form of mind control - It is a lot like meditation, with a specific therapeutic goal in mind - I was surprised about how fascinated everyone here is in learning more about it.

It is not as if clinicians here don't have other things to worry about: like very ill children dying on a regular basis, for example, or seeing the throngs of parents and babies amid the chaotic queues of the OPD. And though they are Buddhists, it is not as if meditation is a part of their culture. In Mahayana Buddhism, practiced here, the monks do the meditation for the lay people, in periods of 3 days, 3 months, or 3 years. As in the U.S., 5 minute meditation sessions are now often held at the beginning of school days, but mindful meditation practice is actually more established in the States.

The Psychiatric ward is at one end of a an old long row of attached departments, some with ambiguous names like "Voluntary Counselling Services - access restricted", and "Heath Help." There are benign uniformed guards posted outside, as they are on the stairwells in the hospital. It is kitty cornered from the ornate archway that marks the entrance to the hospital and a woman's collective that sells water, soda, and mom's, 30N ($.5)) for 5. They are served by friendly women who pick them out of big thermoses. They wear plastic gloves, which makes the process seem very hygienic, though the grounds are littered everywhere with garbage, which dogs sometimes pick through.

Inside the ward is a small anteroom, a check in room, an "ECT" room with a table for electroshock therapy, a lounge big enough for meeting with a patient and a parent, and the patient rooms. There are 8 of them, and depending on the census, they may be coed. A 21 year old on whom I consulted had to share a room with an old man who spoke word salad. Upstairs, there is a large conference room. Like most all buildings in Bhutan, there is no central heating, so it is usually chilly, and dark.

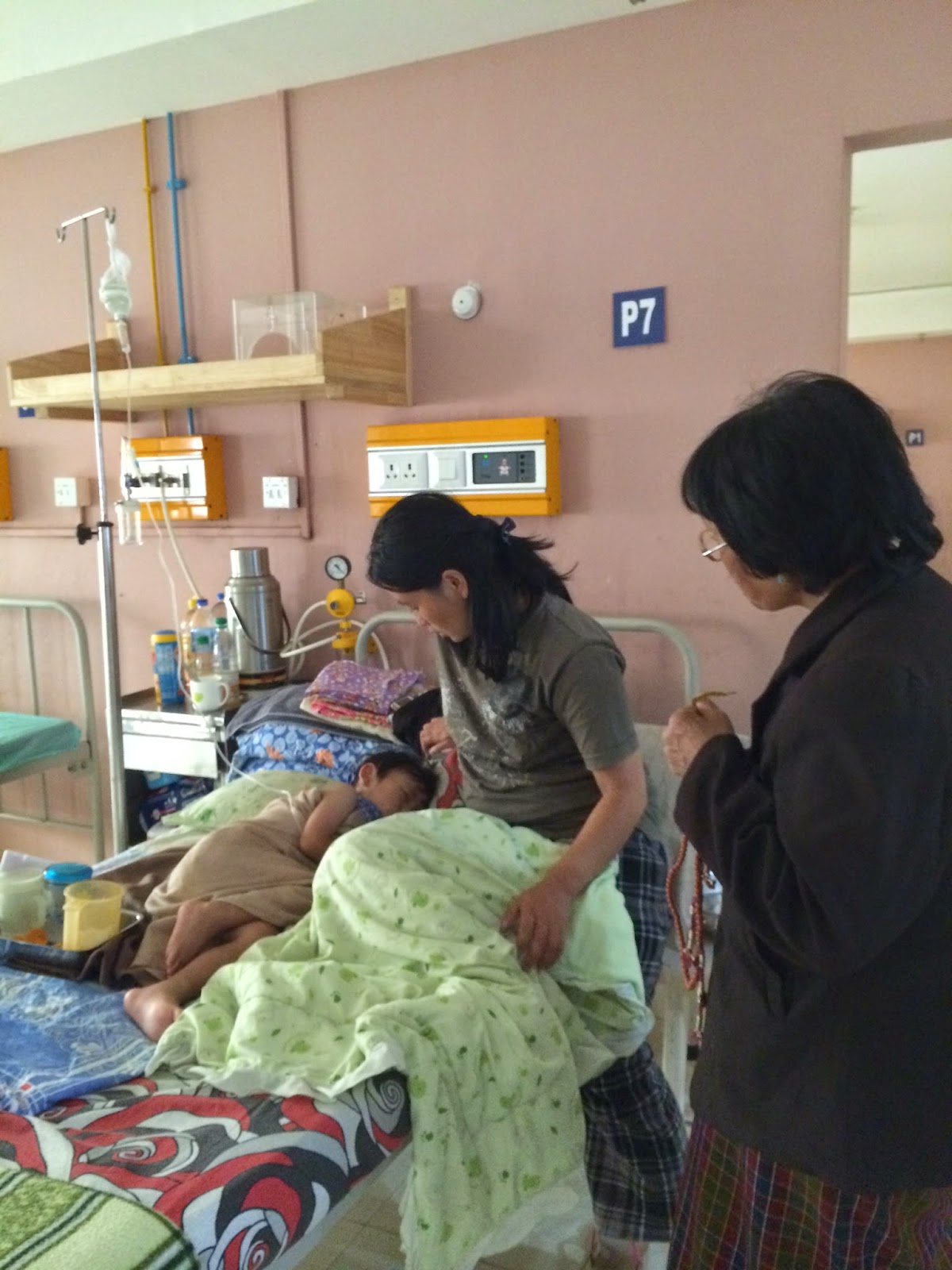

I saw met Tshering in his room and led him to the lounge. Ugen, a therapist in training, accompanied us. Ugen wanted to videotape the session but, when I asked the boy his permission, he declined. Ugen wanted us to see the boy alone, but when I asked Tshering, he asked that his mother come with us. I think patient autonomy is a concept somewhat foreign to Bhutan.

The session itself was difficult, because, as often happens, Tshering's mother was as anxious as he was - maybe more so. Also, though his English was fluent, I'm sure he dreamt, and thought and felt in the Bhutanese language: Dzonka. I found out that he was concerned not only where the girl "had gone" when she died, but about his friends with whom he played football (which we call soccer.) He thought that many of them were "weak" By this he meant thin.

I was able to teach him to imagine him and his friends playing football -- all of them healthy and strong. I also utilized a story from my trek. In the beautiful 4200 meter village of Laya, a fellow trekker and I joined in a football game on the school's muddy, rocky field. It had been raining, off and on, as it had been my entire trek. But then it cleared, and a double rainbow appeared which spread from one end of the village to the other, looking east to the Himalayan peaks. The weather is a good metaphor for our feelings. It can change from bad to good, from cloudy to sunny at any time.

Tshering was entering the developmental stage of abstract thought. A very bright boy, he was pondering not only about our own mortality, but about the origins and extent of the universe, and other questions which have no definite answers. Like all anxious people, he was having a very difficult time with uncertainty. That night, as I was thinking of things I could have introduced to our session, I recalled my own early adolescence, and how I first realized with certainty how our lives were finite.

The Buddhist concept of rebirth was obviously not comforting to this young man.

I later found out that he was being bullied in school, and had a difficult time with his father. During my month here, I have been impressed that though our cultures are very different, the universal struggles among children and adults, are the same.

I was asked a half dozen times to lecture about hypnosis during my stay here. The first talk was on my first full day of work -- to the pediatric attendings and house staff. I showed them a video of my working with an 18 year old patient of mine with Down Syndrome - whom I shall call Bethany. I had seen Bethany as a patient all her life. She had many of the problems of kids with Down Syndrome _ mental retardation, with severe speech problems, tonsillar hypertrophy, and sleep apnea, recurrent ear infections, failure to thrive as an infant, followed now by obesity, and recurrent skin infections. Because of some bullying, and a fear of the alarm bell, she had developed school phobia. She would deal with her anxiety by going to the girl's room and taking off all her clothes. Then she would be sent home.

She also would call her imaginary friend Megan, and Jesus, on her cell phone, on the way to school. This was not that surprising, since her developmental age was around five. Her dad took away her cell phone as a punishment for not going to school. The first intervention I made was to have dad give back her cell phone. These "primary interventions" are as important as the "secondary interventions" we make as doctors or therapists.

Then I taught Bethany simple breathing techniques, with the use of a stone I gave her as an anchor. She was able to learn to breath away her worries. I said that she call her "friend" Megan for help. She could also call Jesus. I always encourage my patients to draw from their spiritual and religious traditions, if they are meaningful to them. She also enjoyed thinking about "my guy" - Brendan - her "boyfriend" at school.

All this took one 1/2 hour session in the office. Since Bethany's symptoms were so dramatic and debilitating, I gave her a prescription for prozac as well. Her mother never needed to fill it. Within one week she was going to school without problems, utilizing my suggestions.

I saw Bethany once more for her school phobia -- two weeks later. This was the session I taped. She showed how she used the stone I gave her to help herself. I reviewed with her how she has learned to "blow out" her worries and fears. She held her breath, puffed her cheeks out and expelled loudly to demonstrate - saying "stupid stupid Matt" (the boy who had bullied her), and "stupid stupid bell".

As I had her breath slowly and calmly, I suggested that she was a brave and strong and smart young woman. I meant it. She was not intelligent in the traditional sense, of course. But she was a good student when it came to self hypnosis --- learning to use it to help herself much more quickly and effectively than others with much higher IQ's.

Then she did something very surprising. "Listen," she said. She cradled her arms over her stomach and rocked them back and forth. I looked over to her mother, who was helping to translate the session for me.

"She's remembering the pictures of when I was pregnant with her," her mom said.

"Listen," Bethany said, pointing. He mom knew what she was getting at.

"She didn't like my maternity dress I wore." We both laughed.

"Listen," Bethany said, one more time. She put her hands up and together, and opened her eyes wide as if discovering the world for the first time.

"She's remembering how she would look when she was a baby, looking out when I held her," her mother interpreted.

"I was your doctor then too," I told Bethany. "And you can remember those comfortable feelings whenever you need to."

It was an amazing moment. Here I was with a young person with cognitive and language delays so significant that most therapists would never even attempt to see her. After all psychotherapy, by definition, is talk therapy. And it was very difficult to understand anything Bethany said. But here she was, demonstrating age regression to create an affect bridge to a time of comfort at the time of her birth, and even before birth. And she came up with all these solutions herself!

After my comment, Bethany entered a deep trance that she maintained for about 5 minutes. She then opened her eyes.

"She really does practice," her mom said, smiling. "She goes to her room and uses the stone… She does do well."

Bethany said something else I didn't understand. "She's saying Thank you for the stone," her mom said.

"Thank you for using the stone," I said.

Then, pointing at me, Bethany said "You're the best doctor ever!"

"You're the best patient ever!" I said.

My teacher and mentor Michael Yapko, with whom my wife and I completed an 100 hour three part workshop this past Spring was asked if patients or clients can really recall and utilize the ideas we introduce in one session of hypnosis for the rest of their lives.

"How long can a good idea last?" he asked, rhetorically.

Forever, of course.

Showing this video, to physicians, to the staff of the Psychiatry ward, and to the staff at Ability center - the first and only developmental center in Bhutan - was helpful for many reasons. Though some of them had limited knowledge of English, they could understand what was going on. They smiled and nodded at the recognition we all share - of the importance of recalling moments of comfort and security to aid us in dealing with challenges and worry.

This was true, especially at the Ability center. It was founded 4 years ago by Beda Giri, a physical therapy assistant who's daughter died of a rare neurodegenerative disease. Beda is a dynamic and resourceful leader who has gotten together a staff of one social worker with an MSW and 5 other staff members. She has attracted support from non profit organizations and a social and developmental pediatrician from the University of California at San Francisco, Brad Berman. "Dr. Brad" is an experienced HVO volunteer who has become a kind of mentor to the center - visiting and teaching here on several occasions, and skyping with the staff in consultation. He also had sound words of advice for me before I came to Thimphu.

Ability is run out of a small but tidy storefront a 5 minute walk from the hospital. Started as a support group, it has grown into a place where children with a diverse assortment of problems ranging from cerebral palsy to ADHD to autism come for group therapy, play with other children, and information sessions for parents.

I was asked to come lead several of these. Since all the therapists have no formal education beyond high school, and there are no speech language pathologists in Bhutan, I was a welcome figure at these sessions.

The questions were sometimes challenging. For example, our HVO coordinator from the hospital brought here son, with autism to see me. "Will he get better, doctor?" she asked.

Another mom asked how she could get her daughter to talk. Her daughter was three and had profound hearing loss from birth. She was essentially deaf. I asked when the hearing loss was diagnosed. At the age of 6 months, her mother answered, through a translator. Did she ever have hearing aides? I asked. She did, her mom said but then they were broken, and she was on a waiting list to get new ones.

NGO's now view Bhutan, with a median per capita income of $2000, and large potential revenues from hydroelectric power, as a middle income country, according to the new WHO representative Orellana Lincetto, who had a few of us over for dinner last night. So a lot of the aide that the kingdom has previously depended on is being withdrawn. There is no money for a new census of health statistics in the country. (Good records of almost any important measure, from infant mortality rates, to deaths from rabies or suicide are lacking). There is also apparently no money for hearing aides, band aides, thermometers, or many important medications that frequently run out on the wards, in the OR, and in the clinics.

Some of the questions have had very obvious answers. For example, a mother asked why her hyperactive child with cerebral palsy was always hungry. I asked about his diet. After some back and forth through translators, I realized that his mom was only feeding him vegetables. This on the advice of a lama. According to tradition, children with seizures should not eat pork nor eggs; children with mental retardations or physical disabilities like CP should not eat meat, eggs, or any protein.

"Your child is always hungry," I said, "because he is starving… The lama is wrong. Children need protein." After ascertaining that the family was not vegetarian, I said that her son needed meat, and eggs. He was probably hyperactive because he is iron deficient.

A recently published text on the history of medicine in Bhutan, written by a Bhutanese pediatrician and Danish public health expert, states that a survey showed that "100%" of the children of Bhutan are iron deficient! I wonder how they actually know, because laboratory measures of serum iron levels are not performed here. The blood would have to be sent to India. Blood counts,which measure anemia, are done.

I said that she should go to the OPD to get Dexorange, the local iron preparation for her child.

I asked (through the staff member who was translating) if she understood. She did. But despite repeating myself emphatically several times, I'm not sure she was convinced.

This morning, I am going with an Ability staff member to a school. Ability provides consultation to the schools for children with developmental disabilities, learning problems, autism, and ADD. So I should get ready.

So much more to write about the rich experiences I've had bringing clinical hypnosis to this mountain kingdom, which did not even practice western medicine until the 1970's. This includes my work with my eldest patient yet, nearly a century old. Pretty unusual for a pediatrician! Will write about this in Part II.

I had already given my first lecture on hypnosis to children, to the Pediatric residents, interns and attendings, on my first full day at JDW National Referral Hospital. After quickly dispelling myths about modern clinical hypnosis - No, it is not like the hypnosis show you saw in India - No, it is not a form of mind control - It is a lot like meditation, with a specific therapeutic goal in mind - I was surprised about how fascinated everyone here is in learning more about it.

It is not as if clinicians here don't have other things to worry about: like very ill children dying on a regular basis, for example, or seeing the throngs of parents and babies amid the chaotic queues of the OPD. And though they are Buddhists, it is not as if meditation is a part of their culture. In Mahayana Buddhism, practiced here, the monks do the meditation for the lay people, in periods of 3 days, 3 months, or 3 years. As in the U.S., 5 minute meditation sessions are now often held at the beginning of school days, but mindful meditation practice is actually more established in the States.

The Psychiatric ward is at one end of a an old long row of attached departments, some with ambiguous names like "Voluntary Counselling Services - access restricted", and "Heath Help." There are benign uniformed guards posted outside, as they are on the stairwells in the hospital. It is kitty cornered from the ornate archway that marks the entrance to the hospital and a woman's collective that sells water, soda, and mom's, 30N ($.5)) for 5. They are served by friendly women who pick them out of big thermoses. They wear plastic gloves, which makes the process seem very hygienic, though the grounds are littered everywhere with garbage, which dogs sometimes pick through.

Inside the ward is a small anteroom, a check in room, an "ECT" room with a table for electroshock therapy, a lounge big enough for meeting with a patient and a parent, and the patient rooms. There are 8 of them, and depending on the census, they may be coed. A 21 year old on whom I consulted had to share a room with an old man who spoke word salad. Upstairs, there is a large conference room. Like most all buildings in Bhutan, there is no central heating, so it is usually chilly, and dark.

I saw met Tshering in his room and led him to the lounge. Ugen, a therapist in training, accompanied us. Ugen wanted to videotape the session but, when I asked the boy his permission, he declined. Ugen wanted us to see the boy alone, but when I asked Tshering, he asked that his mother come with us. I think patient autonomy is a concept somewhat foreign to Bhutan.

The session itself was difficult, because, as often happens, Tshering's mother was as anxious as he was - maybe more so. Also, though his English was fluent, I'm sure he dreamt, and thought and felt in the Bhutanese language: Dzonka. I found out that he was concerned not only where the girl "had gone" when she died, but about his friends with whom he played football (which we call soccer.) He thought that many of them were "weak" By this he meant thin.

I was able to teach him to imagine him and his friends playing football -- all of them healthy and strong. I also utilized a story from my trek. In the beautiful 4200 meter village of Laya, a fellow trekker and I joined in a football game on the school's muddy, rocky field. It had been raining, off and on, as it had been my entire trek. But then it cleared, and a double rainbow appeared which spread from one end of the village to the other, looking east to the Himalayan peaks. The weather is a good metaphor for our feelings. It can change from bad to good, from cloudy to sunny at any time.

Tshering was entering the developmental stage of abstract thought. A very bright boy, he was pondering not only about our own mortality, but about the origins and extent of the universe, and other questions which have no definite answers. Like all anxious people, he was having a very difficult time with uncertainty. That night, as I was thinking of things I could have introduced to our session, I recalled my own early adolescence, and how I first realized with certainty how our lives were finite.

The Buddhist concept of rebirth was obviously not comforting to this young man.

I later found out that he was being bullied in school, and had a difficult time with his father. During my month here, I have been impressed that though our cultures are very different, the universal struggles among children and adults, are the same.

I was asked a half dozen times to lecture about hypnosis during my stay here. The first talk was on my first full day of work -- to the pediatric attendings and house staff. I showed them a video of my working with an 18 year old patient of mine with Down Syndrome - whom I shall call Bethany. I had seen Bethany as a patient all her life. She had many of the problems of kids with Down Syndrome _ mental retardation, with severe speech problems, tonsillar hypertrophy, and sleep apnea, recurrent ear infections, failure to thrive as an infant, followed now by obesity, and recurrent skin infections. Because of some bullying, and a fear of the alarm bell, she had developed school phobia. She would deal with her anxiety by going to the girl's room and taking off all her clothes. Then she would be sent home.

She also would call her imaginary friend Megan, and Jesus, on her cell phone, on the way to school. This was not that surprising, since her developmental age was around five. Her dad took away her cell phone as a punishment for not going to school. The first intervention I made was to have dad give back her cell phone. These "primary interventions" are as important as the "secondary interventions" we make as doctors or therapists.

Then I taught Bethany simple breathing techniques, with the use of a stone I gave her as an anchor. She was able to learn to breath away her worries. I said that she call her "friend" Megan for help. She could also call Jesus. I always encourage my patients to draw from their spiritual and religious traditions, if they are meaningful to them. She also enjoyed thinking about "my guy" - Brendan - her "boyfriend" at school.

All this took one 1/2 hour session in the office. Since Bethany's symptoms were so dramatic and debilitating, I gave her a prescription for prozac as well. Her mother never needed to fill it. Within one week she was going to school without problems, utilizing my suggestions.

I saw Bethany once more for her school phobia -- two weeks later. This was the session I taped. She showed how she used the stone I gave her to help herself. I reviewed with her how she has learned to "blow out" her worries and fears. She held her breath, puffed her cheeks out and expelled loudly to demonstrate - saying "stupid stupid Matt" (the boy who had bullied her), and "stupid stupid bell".

As I had her breath slowly and calmly, I suggested that she was a brave and strong and smart young woman. I meant it. She was not intelligent in the traditional sense, of course. But she was a good student when it came to self hypnosis --- learning to use it to help herself much more quickly and effectively than others with much higher IQ's.

Then she did something very surprising. "Listen," she said. She cradled her arms over her stomach and rocked them back and forth. I looked over to her mother, who was helping to translate the session for me.

"She's remembering the pictures of when I was pregnant with her," her mom said.

"Listen," Bethany said, pointing. He mom knew what she was getting at.

"She didn't like my maternity dress I wore." We both laughed.

"Listen," Bethany said, one more time. She put her hands up and together, and opened her eyes wide as if discovering the world for the first time.

"She's remembering how she would look when she was a baby, looking out when I held her," her mother interpreted.

"I was your doctor then too," I told Bethany. "And you can remember those comfortable feelings whenever you need to."

It was an amazing moment. Here I was with a young person with cognitive and language delays so significant that most therapists would never even attempt to see her. After all psychotherapy, by definition, is talk therapy. And it was very difficult to understand anything Bethany said. But here she was, demonstrating age regression to create an affect bridge to a time of comfort at the time of her birth, and even before birth. And she came up with all these solutions herself!

After my comment, Bethany entered a deep trance that she maintained for about 5 minutes. She then opened her eyes.

"She really does practice," her mom said, smiling. "She goes to her room and uses the stone… She does do well."

Bethany said something else I didn't understand. "She's saying Thank you for the stone," her mom said.

"Thank you for using the stone," I said.

Then, pointing at me, Bethany said "You're the best doctor ever!"

"You're the best patient ever!" I said.

My teacher and mentor Michael Yapko, with whom my wife and I completed an 100 hour three part workshop this past Spring was asked if patients or clients can really recall and utilize the ideas we introduce in one session of hypnosis for the rest of their lives.

"How long can a good idea last?" he asked, rhetorically.

Forever, of course.

Showing this video, to physicians, to the staff of the Psychiatry ward, and to the staff at Ability center - the first and only developmental center in Bhutan - was helpful for many reasons. Though some of them had limited knowledge of English, they could understand what was going on. They smiled and nodded at the recognition we all share - of the importance of recalling moments of comfort and security to aid us in dealing with challenges and worry.

This was true, especially at the Ability center. It was founded 4 years ago by Beda Giri, a physical therapy assistant who's daughter died of a rare neurodegenerative disease. Beda is a dynamic and resourceful leader who has gotten together a staff of one social worker with an MSW and 5 other staff members. She has attracted support from non profit organizations and a social and developmental pediatrician from the University of California at San Francisco, Brad Berman. "Dr. Brad" is an experienced HVO volunteer who has become a kind of mentor to the center - visiting and teaching here on several occasions, and skyping with the staff in consultation. He also had sound words of advice for me before I came to Thimphu.

Ability is run out of a small but tidy storefront a 5 minute walk from the hospital. Started as a support group, it has grown into a place where children with a diverse assortment of problems ranging from cerebral palsy to ADHD to autism come for group therapy, play with other children, and information sessions for parents.

I was asked to come lead several of these. Since all the therapists have no formal education beyond high school, and there are no speech language pathologists in Bhutan, I was a welcome figure at these sessions.

The questions were sometimes challenging. For example, our HVO coordinator from the hospital brought here son, with autism to see me. "Will he get better, doctor?" she asked.

Another mom asked how she could get her daughter to talk. Her daughter was three and had profound hearing loss from birth. She was essentially deaf. I asked when the hearing loss was diagnosed. At the age of 6 months, her mother answered, through a translator. Did she ever have hearing aides? I asked. She did, her mom said but then they were broken, and she was on a waiting list to get new ones.

NGO's now view Bhutan, with a median per capita income of $2000, and large potential revenues from hydroelectric power, as a middle income country, according to the new WHO representative Orellana Lincetto, who had a few of us over for dinner last night. So a lot of the aide that the kingdom has previously depended on is being withdrawn. There is no money for a new census of health statistics in the country. (Good records of almost any important measure, from infant mortality rates, to deaths from rabies or suicide are lacking). There is also apparently no money for hearing aides, band aides, thermometers, or many important medications that frequently run out on the wards, in the OR, and in the clinics.

Some of the questions have had very obvious answers. For example, a mother asked why her hyperactive child with cerebral palsy was always hungry. I asked about his diet. After some back and forth through translators, I realized that his mom was only feeding him vegetables. This on the advice of a lama. According to tradition, children with seizures should not eat pork nor eggs; children with mental retardations or physical disabilities like CP should not eat meat, eggs, or any protein.

"Your child is always hungry," I said, "because he is starving… The lama is wrong. Children need protein." After ascertaining that the family was not vegetarian, I said that her son needed meat, and eggs. He was probably hyperactive because he is iron deficient.

A recently published text on the history of medicine in Bhutan, written by a Bhutanese pediatrician and Danish public health expert, states that a survey showed that "100%" of the children of Bhutan are iron deficient! I wonder how they actually know, because laboratory measures of serum iron levels are not performed here. The blood would have to be sent to India. Blood counts,which measure anemia, are done.

I said that she should go to the OPD to get Dexorange, the local iron preparation for her child.

I asked (through the staff member who was translating) if she understood. She did. But despite repeating myself emphatically several times, I'm not sure she was convinced.

This morning, I am going with an Ability staff member to a school. Ability provides consultation to the schools for children with developmental disabilities, learning problems, autism, and ADD. So I should get ready.

So much more to write about the rich experiences I've had bringing clinical hypnosis to this mountain kingdom, which did not even practice western medicine until the 1970's. This includes my work with my eldest patient yet, nearly a century old. Pretty unusual for a pediatrician! Will write about this in Part II.