On the way to the hospital, sounds of chanting monks, bells, and trumpets

They were not successful. It was our eight death in two weeks. Pneumonia is the leading killer of children in the world. It claims the lives of two million kids a year, most of them in developing countries like Bhutan.

The baby might have also suffered from meningoencephalitis, like so many young patients here. Last Monday we let an infant die quietly, her heart rate and breathing slowing to a stop in the PICU, who had this diagnosis. Her pupils had been fixed and dilated. This death was especially difficult for me, because she had been doing better for a while. The dopamine to support her blood pressure, and mannitol for her cerebral edema had been weaned off. I had allowed her to begin to nurse again.

Her father had asked me, "Will she be ok, Doctor?"

Doctors have a lot of authority here. Students stand when I arrive to give a lecture.

"I can't say for sure," I said. "But it is a good sign that she has begun to nurse again." I'm sure that being a loving parent, the "good sign" is what he remembered.

Dr. Jimba, Dr. Tashi, nurse anesthetist Pema and PICU staff

Dr. Jimba, Dr. Tashi, nurse anesthetist Pema and PICU staff

I worked hard preparing a lecture on encephalitis last week - not that there was that much to say. Even the most sophisticated research, with the most esoteric labs available, done under the auspices of the California Encephalitis Project, have revealed specific pathogens in only 16% of cases. And, like Ebola, there is no cure for any of them.

Shelly told me the news about the doctor with Ebola in New York. I haven't watched TV,

browsed the web, or listened to the news since leaving home September 13. I've tried to avoid news feeds on Facebook (with only partial success, since I have wanted to keep up with friends.) I haven't read a newspaper except for the local paper "The Kuensel" which is the state paper in Bhutan. It only has local news -- lots of stuff about "their Majesties" travel and so on. I can't say I've missed any of it. One does not have to search far for one of the reasons for the relative happiness of people here: the absence of the constant negative nasty news, attacks on our President (blamed for Ebola, no less!), anxieties and fears about everything, daily reminders of the corporate takeover of both our political system and our healthcare system.

Here in Bhutan, they DO worry about global climate change. But there should be a lot more anxiety about illness and death. After all, these deaths from encephalitis qualify as an outbreak. But this does not make the news here. Record keeping is not good. There are no respiratory nor contact precautions. Neither are there gowns, gloves, nor masks, except in the NICU.

Orellana Lincetto, the bright, experienced new WHO representative to Bhutan, who I had over for dinner a week ago Friday, said there is a plan in place for caring for a case of Ebola if it does strike Bhutan. But much more important measures in preventing the spread of infectious disease would be things like putting screens on windows in the hospital to keep flies out, providing soap for all the sinks, and fixing the sinks in the out patient pediatric clinic. Right now the one in Chamber 2, my usual exam room, spits and sputters and threatens to explode, but doesn't produce a stream of water. We go through a lot of hand cleanser.

Scenes from the OPD waiting area. The signs warn of the dangers of polio.

Orellana Lincetto, the bright, experienced new WHO representative to Bhutan, who I had over for dinner a week ago Friday, said there is a plan in place for caring for a case of Ebola if it does strike Bhutan. But much more important measures in preventing the spread of infectious disease would be things like putting screens on windows in the hospital to keep flies out, providing soap for all the sinks, and fixing the sinks in the out patient pediatric clinic. Right now the one in Chamber 2, my usual exam room, spits and sputters and threatens to explode, but doesn't produce a stream of water. We go through a lot of hand cleanser.

Scenes from the OPD waiting area. The signs warn of the dangers of polio.

I joined the intern in the OPD. We admitted two children: a two month old with pneumonia, and a 20 month old with severe stunting, microcephaly and cerebral palsy, from a small village. This child had been "lost to follow up" and had had no care for his malnutrition, developmental delays, or spasticity. She turned blue and stiff from a severe breath holding spell when we looked at her ears.

The previous day, I had admitted a normal child about the same age who began to seize while waiting in the queue to be seen. She had a febrile seizure.

Patients and families with us in the OPD

I went to check on her on the ward and a child we had diagnosed with Kawasaki's Disease. This 3 year old boy was now sicker. He had developed pneumonia, probably nosocomial (hospital acquired). Dr. Tashi had put him on a new antibiotic. He has had a fever for two weeks now. His rash, which had disappeared, was back.

Patients and families with us in the OPD

I went to check on her on the ward and a child we had diagnosed with Kawasaki's Disease. This 3 year old boy was now sicker. He had developed pneumonia, probably nosocomial (hospital acquired). Dr. Tashi had put him on a new antibiotic. He has had a fever for two weeks now. His rash, which had disappeared, was back.

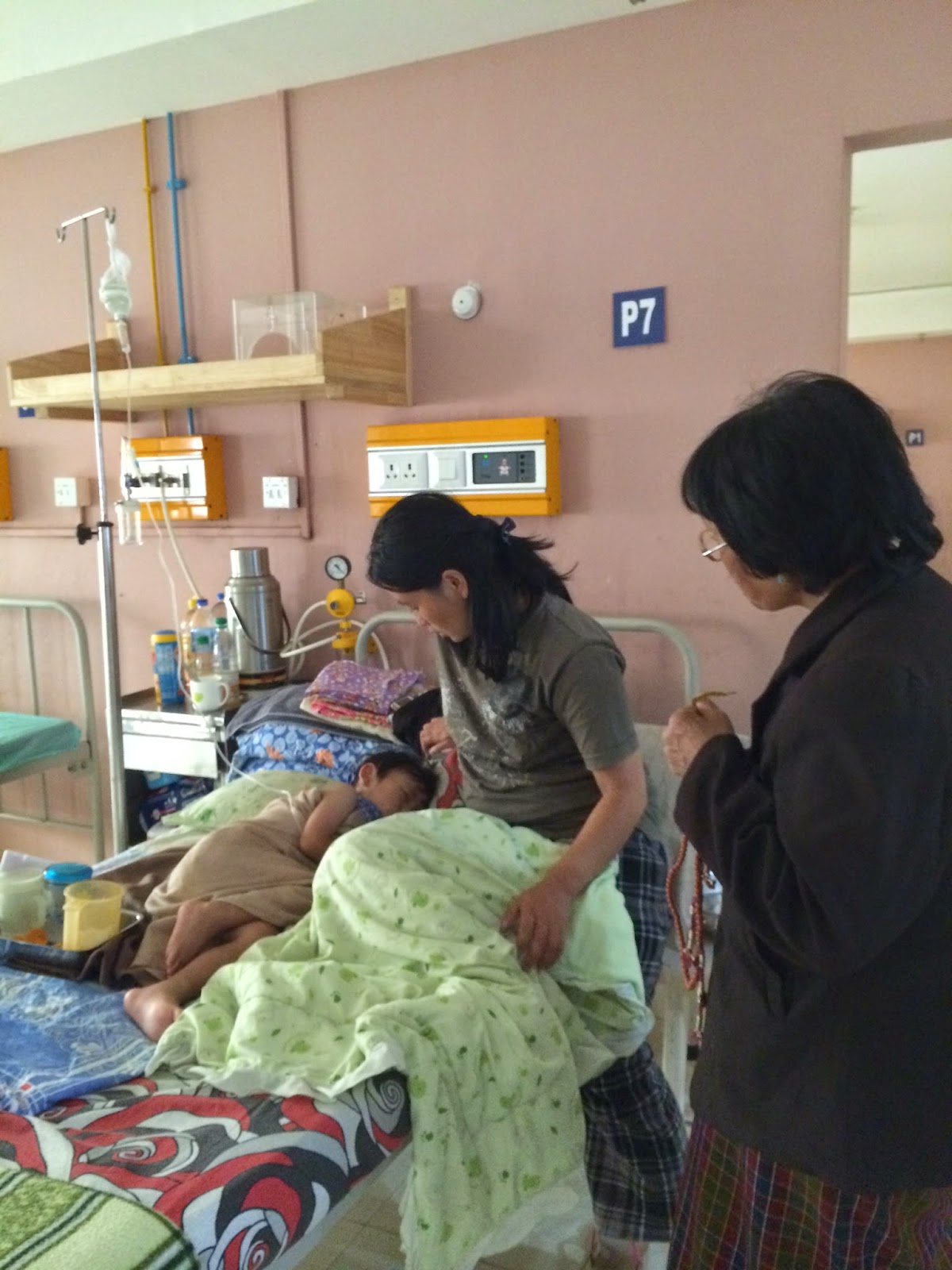

Grandmother with prayer beads chanting and nurse improvising with webbing to hang IV as no IV set ups were available

I asked a nurse for a bandaid for a cut I had. The hospital does not have the money for them, so here she is in the treatment room, picking out some gauze I can tape on instead.

Dr. Tashi was in the PICU. She was reviewing all the recommendations for Kawasaki Disease on her tablet. The physicians here are as plugged in to Up-to-Date, Medscape, the AAP Red Book and other sources of the most recent medical guidelines and research as my colleagues back home. In fact, there is now, a new program, Pemsoft, installed by a former HVO pediatrician, Kathy Gallagher, who came here as a tourist last week. It is being provided free to developing countries by the group KidsCare. The problem is, of course, that many of the recommendations for tests and medications are impossible to follow here, since they just aren't available. They have to improvise with what they have.

As I have every day, I checked in on a 10 year old boy in the second bed in the PICU. He has been in the hospital for two months. He has a rare and serious form of glomerulonephritis which has caused renal failure. He has been on hemodyalysis his entire hospitalization. Now he has developed cardiomegaly and pulmonary edema. He was in respiratory failure. Three days ago, Dr. Tashi had suggested intubation, but his father, who has been at his bedside constantly, refused. He has been given maximum amounts of oxygen by mask instead.

He is somewhat better today, clinically, after more morphine and lasix. One of the routine measurements back home would be arterial blood gases. But the machine that does this measurement in the hospital is frequently "down", and the kits they have in the PICU here don't match the machine. Besides, he is "jumping around" too much, and the experienced nurse anesthetist, Pema, who runs the unit fears sedating him too much. The heads of department in the hospital have approved his going to Calcutta for a kidney transplant.

"He is going on Monday" Pema said.

"By medical transport?" I asked "Helicopter?"

"No, on Druk Air" he said.

"On a regular passenger flight?" I asked.

"Yes," he said. "With me. It's difficult, in peak tourist season. We had to wait for an open seat…

"It's kind of funny actually," he smiled. "We book as many seats as we need. I have the IV and the tubing hanging. This flight is a short one. I go on many many flights. I've had to go to Bangkok with a patient who had been on a ventilator. I had to bag him the whole way. Six hours."

He shook his hand to show how tiring it was. "The oxygen tanks on board are too small. We have to bring our own."

I chatted with Dr. Tashi in the little cubicle where we take breaks for tea, momo's and rice. We were joined by a cardiologist interested in seeing the movie "Fed Up". I brought a copy of the DVD here to Bhutan. My plan was to show it to as many people as I could, hopefully the Health Minister who I met last year with Shelly. In a country as small as Bhutan, with no fast food chains, and virtually no fat people, there is a chance to prevent the obesity epidemic which is wreaking havoc on the health of American citizens, as well as the Chinese, and virtually every developed country.

My dream is that maybe the Bhutanese will be motivated to pass a tax on soda and other sugary foods, the way Mexico and other countries are doing.

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. Literally.

It doesn't look like the meeting with the Health Minister will happen. And physicians have been too busy thus far. But I did show it to the third year nursing students at the Royal Institute of Health Sciences (RIHS).

I introduced it as a cautionary tale. "You don't have this problem," I said to the waiting students, "But this is what can happen if you give up the traditional Bhutanese diet for the the junk food we eat in the States."

They had waited for me for 40 minutes. (As often seems to happen here, I was given the wrong time for the showing. I've also been given the wrong places, had lectures cancelled at the last minute, told to meet a contact person who was not there, searched the spacious offices in the RIHS for the person I was supposed to meet, finding they were all empty as the faculty or administrators were all "at meetings" or "running errands")

The students were patient. They stood up when I entered the room. I was served tea in a china cup, cookies and fruit. I joked to the student helping me that here I was, showing a movie about the dangers of sugar, enjoying sugary snacks. The student didn't get the humor. Often jokes get lost in the translation to another language or culture.

But young people here certainly have a sense of humor. It's perhaps a little different from ours. They were transfixed by the film. They had a lot of good questions. But during the movie, when there were scenes of a very obese girl crying repeatedly, students laughed. A Butanese friend said that people think is funny when someone cries "too much".

Students, and a dog who wandered in, watching "Fed Up"

And tonight I was on my way to what turned out to be a wonderful nursing school talent show to which I was invited - it was as if my friend and I were at an arts and music school production, filled with traditional Bhutanese, Tibetan, and Hindi song and dance, lots of hip hop, and everything in between, with lots of cheering and merriment -- when a young man with severe spastic diplegia passed by with his walker, accompanied by two friends. It was dark. He fell over the lane divider as he entered the hospital parking lot. He and his two friends laughed as they all struggled to get him to his feet. I asked if I could help them.

"No thank you sir, Karincha-la" one young man smiled, as they succeed in righting their friend. Then still smiling, they continued on their way.

The cardiologist warned us both of the dangers of the deep fried snacks Dr. Tashi and I were eating, brought by the nurses from the Hindi festival happening this last week. Stores and offices in India have been closed; noises of firecrackers and flickers of red and white sparklers fill the air at night. I enjoyed the sweet greasy dough anyway, marveling at how the cardiologist looked so cool and smart in his crisp white coat and sweater vest in the heat of this tiny anteroom. We talked about the film showing. I also asked for an extra hour in which I could offer some suggestions to the Pediatric staff, based on the research I did for my lectures during my month here, and my years of experience as a pediatrician in the Unites States.

Dr. Mimi is away, after being invited their by a former volunteer. I said Good bye to her after spending a short time the previous day with her in the development clinic. She asked for my advice on a child with Williams Syndrome and ADHD, and a child with severe autism. I told her about the solid scientific evidence that eliminating artificial food coloring helps reduce hyperactivity and other symptoms of ADHD.

She said that she was sorry that we had so little time to talk during my stay.

"You must come back again," she smiled, "for a third time. Three shall be your lucky number! "

Dr. Mimi discussing a patient with me in the Developmental Clinic

Dr. K.P. is rarely available as he is interim president of the new graduate school of medical education. Which will leave Dr. Tashi as the only pediatrician in the hospital (outside of the two neonatologists, both of whom are unpaid). Unless the one pediatrician in the south of the country can be brought here. But that is currently "in process".

Soon I was off to my last stop of the day: the Psychiatric ward, to follow up on a 21 year old woman admitted yesterday. I was asked by the American psychiatrist volunteer, Dr. Allen, to see her. She had a long history of "giddiness", treated as seizures, but often a sign, if not the only sign, of depression here. She had stopped speaking after having an argument with her mother.

It's amazing how interested everyone here has been in my skills in clinical hypnosis --- from nurses, to physicians, to therapists, to patients. In my 25 years at Baystate Medical Center back home, and in my 22 years at my private medical practice, I have never been asked to speak about these skills or my clinical experience in helping hundreds, if not thousands of patients. But here, I have been asked to lecture about hypnosis to nurses, nursing students, community health workers, psychiatric staff, and pediatricians, and to see patients ranging in age from 11 to 96!

More on this in the next post.

You're doing some good work

ReplyDelete